Outline:

The holidays are a time for celebration and relaxation. Wine accessories can take the hassle out of hosting your own wine tasting party this year, and we're here to help! Wine accessories can be used to help serve up wines and champagne in style while also making it easier than ever to open bottles with just one hand - that's right, no more chasing after pesky corkscrews or trying to use your teeth!

Whether you're looking for classy ways to serve beverages or need some new tools for opening bottles at home, these five items are sure to keep any hostess organized this season.

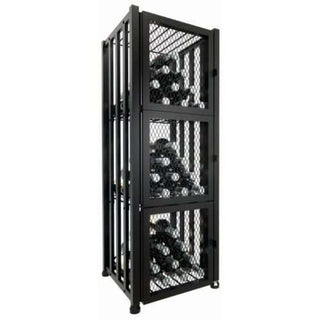

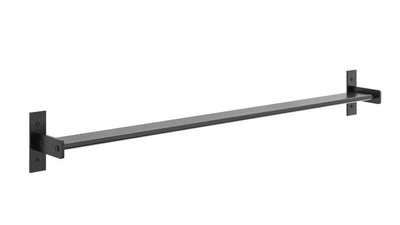

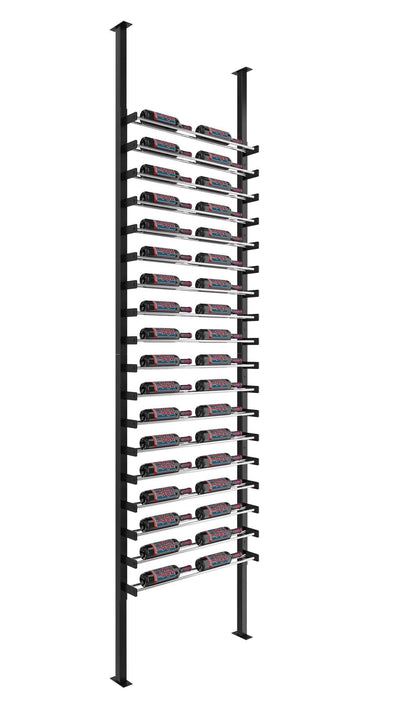

Wine Racks

Wine racks come in all shapes and sizes, but they're essential for any wine lover looking to organize their collection. Not only do wine racks keep bottles off of the ground and in a designated space, but they also make it easy to see and select your favorite wines. Freestanding wine racks can be placed almost anywhere or wall-mounted wine racks that save space.

Your next dinner party just got a whole lot more organized. Wine racks are the perfect way to keep your countertops clear while still having access to bottles on hand at all times!

Bottle stands are another great way to keep countertops clear while still making it effortless to pour wines for your guests. Wine bottle holders, like wine racks, can be found in a variety of different styles and materials that suit any space or theme you may have. There's something for everyone, from modern silver showcases with glass doors to rustic wooden bases with built-in handles!

Wine Accessories Set

A practical wine accessory is an absolute must when hosting events this season. You'll want everything at hand when opening bottles on the fly (we've all been there), but don't forget about style too! These beautiful sets are just what you need to keep wines organized, whether it's laying out the glasses or filling them up for your guests.

Last but certainly not least, wine openers are another necessity that will make serving up bottles of wine an absolute breeze. You can find manual and electric wine bottle opener sets in various styles that suit any countertop decor. So go ahead and grab a glass - we've got everything covered!

Wine accessories made from stainless steel with corkscrews, foil cutter knife, and drip ring tool holder are all inside the classy box, making this product look much more expensive.

Wine Coolers

A wine cooler is another great item for anyone who wants to save space or have extra storage in their kitchen. Wine coolers look just like refrigerators and often come with an attached stemware rack so that you can store glasses safely without worrying about breakage. Wine chillers also help maintain a specific temperature, making it easier than ever to enjoy chilled wines whenever the mood strikes you!

Wine coolers are perfect for storing any extra wine bottles you may have, and they come in a variety of sizes to fit any space. With just a little bit of preparation, you can easily store all of your wines in one place and keep them at the perfect temperature!

We hope that these wine accessories help make your holiday season a breeze. From organizing your collection to keeping beverages chilled, we've got everything you need to celebrate in style! Cheers!

Wine Glasses

Dinner parties are incomplete without attractive wine glasses, and there are a variety of styles available to suit any decor. Wine glasses come in many different colors, shapes, and materials that can be personalized for each guest or used as matching pieces throughout your home.

Wine glassware is an absolute must-have if you're looking to impress guests without going too far overboard on decorations. The suitable wine glasses will make it effortless to serve up the perfect drink at any event - so don't forget about them!

Wine glasses are not just for serving up wine, either! Wine goblets can also be used as the perfect vessel to serve fruit juice or other beverages at a party. And don't forget about champagne flutes - they're an absolute must if you want your bubbly drink to look its best!

Wine Cart

You don't want to be gone from the party for long periods, rummaging through cupboards for your supplies, or rushing back and forth to the kitchen. A wine and bar cart solves all of these issues. It's an ideal location to store all of your ingredients, including bottles, stemware, alcohol, opening equipment, and so on. Wine carts are the perfect way to keep your kitchen looking chic while still functional.

Whether you're hosting a dinner party or enjoying drinks with friends, wine and bar carts will be sure to impress - without breaking the bank! Wine accessories can easily dress up any countertop decor so that everything is within arm's reach for when you need it most. Wine bars have never looked so stylish.

You may use the cart as a self-serve station for your visitors or a mobile bartending station for yourself or hire staff. A mobile wine cart may be used as a secondary drink station in another area, keeping your bar from becoming clogged if you don't already have a wet bar in your home. Wine bars can be used as a casual buffet table for appetizers and desserts, too! Wine accessories are the perfect way to make any party feel like an elegant event.

Looking For Wine Accessories

Wine Coolers America's website is an excellent resource if you're searching for a present for your wine-loving family member or want to refresh their collection with some new accessories during the holidays.

We have everything from wine racks and wine credenza to other wine furniture that will put a smile on any recipient's face this holiday season. Visit our site today or give us a call!